Industrialized food is dependent on modern infrastructure for its production, processing and distribution. On its way from producer to consumer, the food that ends up in our kitchens is often transformed beyond recognition, and it moves on a global scale. Modern food often undergoes complete deconstruction and reconstitution before it arrives in our refrigerators, even if the products we purchase seem natural and straight from the farm. Many agricultural products are broken down into their chemical compounds and nutritional building blocks; new products are created through the recombination of these parts. Whether something is lost in the process or if healthy nutrition is nothing more than the right ratio of nutrients remains an active question in nutritional science and beyond.

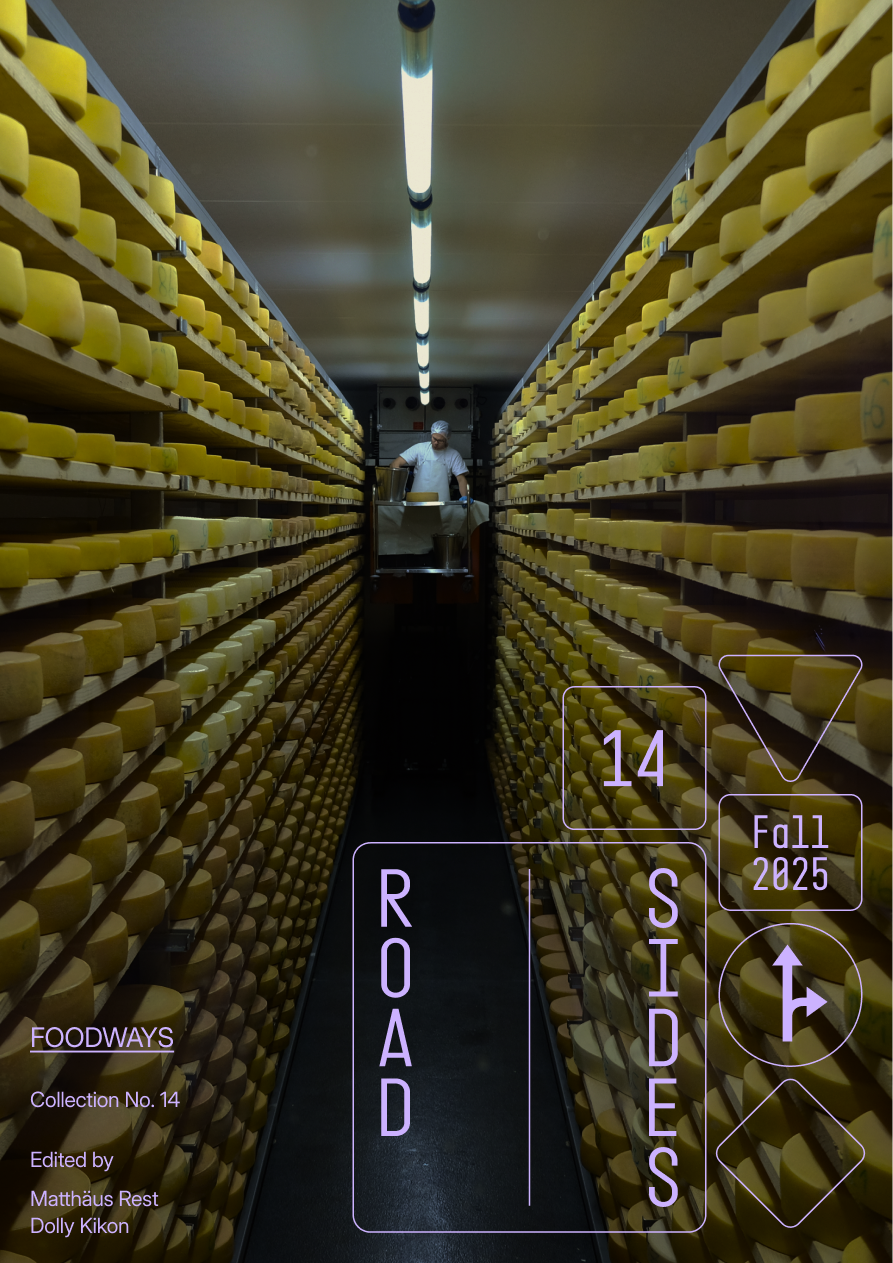

One central problem with many foodstuffs is that they spoil quickly. This time sensitivity makes the relations between food and infrastructure particularly complicated and unequal, as those who control the systems for moving and processing food have exorbitant power over those who produce it. Before the invention of modern infrastructures, many raw foodstuffs had to be processed quickly, in relatively small batches, close to the point of origin. Across the planet and for millennia, people have come up with a host of different methods to transform these into forms that are stable, often for years, and therefore storable and tradeable over long distances.

The contributions to this collection show the value and importance of an understanding of infrastructures that goes beyond their technical properties – these are much more than complex structures that simply move things. Rather, the articles employ a compellingly wide definition of infrastructure that includes community, kinship, memories, social connections, and things like pesticides, Indigenous rice varieties and community cookbooks. For decades, the term foodways has been used in food studies and beyond to account for the multifaceted relations between food, culture and identity – how the things we eat condition who we are and how we understand ourselves in relation to the world and to others. In line with the general thrust of Roadsides, we understand the term to focus on the ways food needs infrastructure to come into, move through and be in the world.

Food and infrastructure interact in multiple ways. Industrialized food is dependent on modern infrastructure for its production, processing and distribution. On its way from producer to consumer, it is often transformed beyond recognition, and it moves on a global scale. Bart Penders and colleagues (2014) use the difference between catching a fish and buying fish fingers at your neighborhood supermarket to drive home this point. Food often undergoes a complete deconstruction and reconstitution before it arrives in our refrigerators in a form that seems natural and straight from the farm. In a documentary film Das System Milch (2017), Aart Jan van Triest, head of marketing at the Dutch multinational dairy cooperative FrieslandCampina, proudly proclaims “We are from grass to glass,” and continues by comparing his company to a refinery, because a dairy plant transforms a single raw material into a vast array of products that “magically come out.” Where the analogy between oil and food breaks down is the fact that many foodstuffs spoil quickly. This time sensitivity makes the relations between food and infrastructure particularly complicated and producers such as dairy farmers dependent on the regular pick-up of their output.

Food and infrastructure invite us to dwell on the circulation of goods and their attendant power networks. In resource frontiers around the world, existing infrastructure that allows the movement of comestibles such as tea and cash crops are facilitated by militarized structures of power. Tracing the nexus between market, capital and violence, we look at the way infrastructure both delivers and distracts from our knowledge of food production. For instance, historian Jayeeta Sharma (2011) draws attention to the instrumentalized violence of railroads that delivered tea from the frontiers of South Asia to ports like Kolkata and London. Non-industrialized forms of food production, on the other hand, rely on very localized materials to engineer the transformation of vegetables, meat and fish. Artisanal practices of curing, fermentation and pickle making expand the notion of infrastructure to include social and cultural relationships and practices.

Our interests in this issue go beyond understandings of infrastructure simply as things that move other things. We invite contributions that explore, but are not limited to, the following questions:

Das System Milch. 2017. Directed by Andreas Pichler, produced by Christian Drewing.

Penders, Bart, David Schleifer, Xaq Frohlich and Mikko Jauho. 2014. “Preface: Food Infrastructures.” Limn 4. https://limn.press/article/preface-food-infrastructures/

Sharma, Jayeeta. 2011. Empire’s Garden: Assam and the Making of India. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.